Mosaics, those captivating assemblages of color and texture, represent far more than mere decoration. They are enduring testaments to human ingenuity, artistic expression, and the desire to transform the mundane into the extraordinary. From their humble beginnings in ancient Mesopotamia to their vibrant contemporary manifestations, mosaics offer a rich tapestry of history, culture, and technical innovation.

The Dawn of Christian Mosaics: Illuminating the Divine

The adoption of mosaic art by the early mosaic Christian artist of the 4th century marked a watershed moment in the history of both the art form and the religion itself. Following centuries of persecution, Christianity gained imperial recognition under Constantine, ushering in an era of unprecedented growth and influence. As the church expanded, its leaders faced the challenge of effectively communicating complex theological concepts to a diverse congregation that included both educated elites and illiterate laborers. Mosaic proved to be the ideal solution.

Imagine stepping into the Basilica di Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, one of the oldest churches in the city. As your eyes adjust to the dim interior, you’re immediately struck by the shimmering gold mosaics that adorn the triumphal arch and the nave. These mosaics, dating back to the 5th century, depict scenes from the Old Testament, rendered in vibrant colors and intricate detail. The gold tesserae, meticulously arranged to catch and reflect the ambient light, create an ethereal atmosphere that seems to transport you to another realm.

Santa Maria Maggiore – Mosaic in the Triumphal Arch – showing Bethlem (Wikipedia Commons)

Santa Maria Maggiore – Mosaic in the Triumphal Arch – showing Bethlem (Wikipedia Commons)

The strategic use of gold was a key element in the success of early Christian mosaics. Gold symbolized divine glory and transcendence, and its reflective properties enhanced the overall luminosity of the artwork, creating a sense of awe and wonder. Moreover, mosaics were far more durable than painted frescoes, which were prone to deterioration in the damp environments of early churches. This durability was particularly important for a young religion seeking to establish its institutional foundations and project an image of eternal truth through its Christian mosaic artwork tiles.

Beyond their practical advantages, early Christian mosaics served as powerful visual metaphors for the Christian community itself. The laborious process of assembling thousands of individual tesserae into a unified whole mirrored the coming together of diverse individuals in faith to create something far greater than themselves.

Byzantine Splendor: Reaching Artistic Zenith

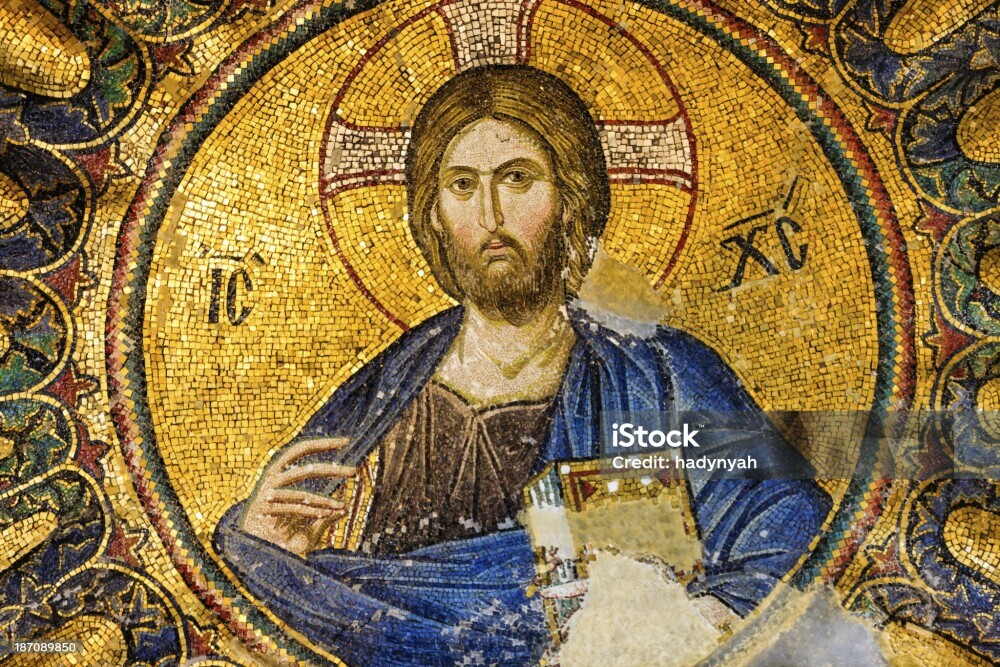

The Byzantine Empire (also known as the Eastern Roman Empire) elevated Christian mosaic art to unprecedented heights, developing sophisticated techniques that maximized light reflection and created seemingly weightless images of Christ, the Virgin Mary, and saints that appeared to float in golden infinity. The Hagia Sophia in Istanbul, originally built as a Christian cathedral in the 6th century, stands as a testament to the unparalleled artistry of Byzantine mosaicists. Its vast dome, adorned with glittering mosaics, creates a breathtaking spectacle that has inspired awe for centuries.

Byzantine artisans mastered the art of setting tesserae at slight angles to one another, creating dynamic surfaces that seemed to shimmer and pulsate with inner light. They also developed a wide range of vibrant colors by adding metallic oxides to molten glass, enabling them to create incredibly detailed and expressive figures. The mosaics of Ravenna, Italy, particularly those in the Basilica di San Vitale and the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia, offer further evidence of the technical virtuosity and spiritual depth of Byzantine mosaic art.

Hagia Sophia – Istanbul (13th Century)

Hagia Sophia – Istanbul (13th Century)

The Renaissance and Beyond: Shifting Tides

The Renaissance brought about a general decline in mosaic production as fresco painting dominated artistic innovation. The Renaissance emphasis on naturalistic representation, perspective, and the subtle modeling of forms proved more readily achievable through painting techniques. Artists like Michelangelo and Raphael could create effects in fresco that would be extraordinarily difficult to replicate in mosaic.

Nevertheless, the mosaic tradition persisted, thanks to the dedication of Venetian workshops that maintained Byzantine techniques. St. Mark’s Basilica in Venice continued commissioning mosaics well into the Renaissance era, often to complete medieval projects. However, mosaic during these centuries functioned more as architectural completion of medieval projects rather than as a primary vehicle for cutting-edge artistic experimentation.

A Modern Revival: Reimagining an Ancient Art

The modern period, beginning in the late 19th century, witnessed a remarkable revival of mosaic art. The Arts and Crafts movement rediscovered mosaic’s decorative potential, while Art Nouveau designers like Antoni Gaudí integrated mosaic into revolutionary architectural visions. Gaudí’s Park Güell in Barcelona is a prime example of this innovative approach, showcasing the vibrant colors, organic forms, and whimsical designs that characterized Art Nouveau mosaic.

The 20th century saw mosaic embrace abstraction, with artists recognizing that the medium’s inherent fragmentation aligned perfectly with modernist aesthetics. Artists like Sonia Delaunay and Fernand Léger incorporated mosaic into their abstract compositions, exploring the expressive potential of color, texture, and geometric form.

Contemporary practitioners continue to expand mosaic’s possibilities, incorporating new materials and conceptual approaches that ancient artisans could never have imagined.

By ferran pestaña – Flickr: Gaudí – Parc Güell 12, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1675232

By ferran pestaña – Flickr: Gaudí – Parc Güell 12, CC BY-SA 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1675232

Technical Developments: Refining the Craft

The evolution of mosaic construction techniques has been crucial to the art form’s longevity and adaptability.

Direct Application:

As mentioned earlier, this method involves placing tesserae directly onto the intended surface. It’s ideal for curved surfaces and small-scale projects, offering artists the flexibility to make spontaneous creative decisions.

Indirect Transfer:

This technique, developed to address the limitations of direct application, involves arranging tesserae face-down on temporary backing material. The mosaic is then transported to its final location and installed. This method is essential for large-scale, flat installations.

Double Indirect:

The double indirect method, using fiberglass mesh as a support system, offers a significant technical advancement. It combines the visual accuracy of the direct method with the logistical advantages of the indirect method, enabling artists to fabricate extensive works within controlled studio environments.

Material Innovations: Expanding the Palette

The history of mosaic art is also a history of material innovation. Ancient mosaicists relied on naturally colored stones, while Byzantine artisans revolutionized the form through their use of glass tesserae.

Contemporary artists now embrace a wide range of materials, including recycled glass, ceramics, mirrors, and even industrial waste. This emphasis on sustainability reflects a growing awareness of environmental issues and a desire to create art that is both beautiful and responsible.

Contemporary Expressions: A Kaleidoscope of Styles

The contemporary mosaic landscape is characterized by its remarkable stylistic diversity. From minimalist mosaics that explore geometric precision to maximalist works that revel in color and ornamentation, there’s a style to suit every taste.

Some contemporary artists use mosaic to engage with digital culture, creating pixelated imagery that references screen-based media. Others pursue traditional representational goals with decidedly modern subjects.

Democratizing Creation: From Elite to Everyone

The support structure for mosaic art has undergone a fundamental transformation, democratizing both creation and access in ways that ancient artisans could never have envisioned. Once an exclusive symbol of imperial authority and ecclesiastical power, mosaic has evolved into an accessible medium for collective creativity and public expression.

Community mosaic projects bring together diverse groups of people to create artworks that celebrate local identity, commemorate shared history, or beautify neglected spaces. Schools worldwide use mosaic as an educational tool, teaching art, mathematics, history, and collaborative problem-solving.

Enduring Relevance: A Future Forged in the Past

From its ancient Mesopotamian beginnings to its multifaceted contemporary manifestations, mosaic art exemplifies humanity’s persistent creative spirit and remarkable adaptability across changing circumstances. Its extraordinary longevity stems from an ongoing conversation between historical tradition and contemporary innovation.

Today, mosaic thrives as an inclusive and dynamic medium, finding new applications in public installations, residential and commercial interiors, therapeutic contexts, and community development initiatives. The art form’s comprehensive impact—uniting visual splendor with practical purpose, individual artistry with collective narrative, ancient technique with contemporary concern—guarantees its continued significance in human culture for generations to come. As new materials emerge and cultural values evolve, mosaic will undoubtedly continue adapting, proving once again its timeless capacity for renewal and relevance.

Affiliate Disclosure

Here’s a little transparency: Our website may contain affiliate links. This means if you click and make a purchase, we may receive a small commission. Don’t worry, there’s no extra cost to you. It’s a simple way you can support our mission to bring you quality affiliate marketing content.